The Cabinetmaker’s Compromise: A Commode and the Changing Aesthetic of French Canada

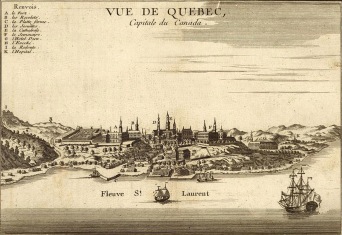

The increased settlement of New France as a fur-trading colony in the late 17th century led to the subsequent development and expansion of the region’s interior. As towns and cities grew, so did their capital, creating a class of wealthy merchants apart from the well-to-do officers and officials. This was most evident in Montreal, as it was the “westernmost point accessible by ocean-going ships” at the convergence of the St. Lawrence and Ottawa rivers, thus controlling the passages to the Great Lakes and the interior fur-trading regions. In Montreal, tertiary sectors of the fur trading economy grew to accommodate new inhabitants, transforming the small town into the economic hub for the French fur trading industry. During this time, population growth in the colony was steady, but in Montreal it appeared more accelerated, ranging from a few hundred in the later part of the 17th century to approximately 7,500 in 1760. With these new inhabitants in all socio-economic classes came a rising demand for domestic industries in providing shelter and furnishings. It was these patrons of woodworkers, carpenters, and cabinetmakers that would dictate the styles of French Canada’s decorative arts, leaving behind beautifully carved and decorated pieces of vernacular furniture.

Top lot of the day, a French Canadian carved chestnut bombe-form commode, sold with buyer’s premium for $77,025.

August 11th, 2012 was a pristine day for an auction in Marlborough, Massachusetts. Skinner, Inc. was holding their annual August Americana sale at their newly acquired Marlborough location. A multitude of stunning pieces of American decorative arts and furnishings were up for sale, including a Dunlap-school chest, a J.W. Fiske butterfly weathervane, a carved Hadley chest, and even a one-room summerhouse. However, none was more exciting than the top grossing lot of the day, a French Canadian butternut bombe commode, hammering at $65,000 (fig. 1). This was a piece that garnered much attention from dealers and collectors alike due to its rare form, old surface, and finely executed carvings. To put it simply, this piece was astonishing.

This essay will consider the implications of changing aesthetics, fashions, and demographics within a developing French Canada on domestic furniture design. The bombe commode detailed above, considered a masterpiece by Canadian collectors, will be attributed to a school of carvers by examining the stylistic motifs they employed. The significance of this piece as the perfect representation of the transitional period of styles in French Canada and possibly the best example of vernacular furniture produced in Montreal warrants this further research. This analysis will be based on carved Rococo friezes and the artisans’ underlying symbolism, understanding of lines and proportion, and comparable documented examples. While it is unfortunate that construction details cannot be ascertained as the commode had been sold and transported by the time of my employment at Skinner, the aesthetic merits of this piece are strong enough and so unique that the attribution is unmistakable…